Larksong, words by Jeremy Hooker, artist’s book by Liz Mathews

Greetings for April and all good wishes from Potters’ Yard in these sad and difficult times. I’m working at home as usual with my partner Frances in our shared studio, so apart from how very quiet it is, and an unusual interest in food shopping, our working life is not much different from our normal daily routine. But the exhibition I was preparing for, which was due to open in early May, has now been postponed until next year, and all the other events I have scheduled for this year are cancelled, suspended or postponed in the uncertainty. And of course these things that I’d normally think of as major disasters are the least of our worries.

One of the things I’ve found most comforting and uplifting in these last few weeks has been the extraordinary blossoming of goodwill that has turned our society into a true community, with people doing their utmost to contribute to the good of their fellow humans. And it’s a good thought that though we’re alone in our homes, isolated from physical contact and proximity, we can still be together in social ways, keeping in touch and sharing things that bring us together virtually. I love this inspiring video forwarded by my friend Priscilla in America (and originally sent to her by artist, calligrapher and musician Jan Owen), showing musicians from the Toronto Symphony Orchestra playing Appalachian Spring together – though they are each in their own homes.

So I’m aiming to do as much online as possible, to focus on spring and share some rainbows of hope and flashes of light – and bring you here on this online galleryblog Daughters of Earth some private views in the next few weeks, for viewing at home, away from the ebb and flow of the outer world:

This paperwork is called Prism II, and it’s on handmade paper (70cm x 50cm approx), lettered in acrylic paints applied with a pen improvised from a wooden clothes-peg. I love to use odd lettering tools – bits of driftwood, sticks from trees – and I like to choose something appropriate to the text. Here Winifred Nicholson is talking about a happy home environment – the words are from her article called ‘I like to have a picture in my room’ – and the clothes-peg has very domestic, almost intimate connotations, some of which can perhaps be transferred into the letters as they’re formed. It’s a nice tool to use for this purpose too, as the flat, absorbent top edge of the peg makes a great italic nib, but without the control of a ‘proper’ pen. And without the little dip in the nib that helps regulate the flow of the ‘ink’, you get a much more free, irregular ink-flow – in fact the ink does what it wants to, rather than what you think it should. I like the materials I’m using to contribute their own life to the work we’re making together, and here, this irregularity lets a lot of light into the form of the letters – soft broken edges on the absorbent paper, no hard edges or straight lines. And light through colour is the essence of the rainbow, the prism breaking up the lightwaves into their constituent hues.

I’m still working on the last few paintings and drawings for my exhibition, now re-scheduled for next April – so the pressure’s off, but the structure of my working week is keeping me sane, so I’m sticking to it. The exhibition – at London’s lovely Burgh House – was to have been called The Prospect of Happiness – and it’s now known as Postponed The Prospect of Happiness – which is almost too poignant. So I’m trying to inject a note of optimism and hope into the artworks I’m making:

This is The Prospect of Happiness, on handmade paper (about 70cm x 50cm) with watercolour paints mixed with Thames water, and lettered with a Thames driftwood stick. The words are from Frances Bingham’s novel The Principle of Camouflage, and the ‘prospect’ is the view from high on Hampstead Heath, down across London, to the downs on the south side – a view very familiar to us both from our local walks – especially on a clear spring day. The ‘tree-crowned hill’ is perhaps Boudicca’s barrow – which features in Frances’ most recent book London Panopticon as the end of a pilgrimage – the view then being at twilight. I like to think that though it’s not so easy to get to the actual place at the moment, this view and all it contains and represents is ever-present in our minds.

This is Blake’s London, a paperwork I made last week for the exhibition. I’ve been thinking about this piece for a long time, and it has finally come together. It’s on handmade paper (approx 30cm x 42cm) and the words are from Blake’s Jerusalem – not the great anthem we sing (And did those feet…) – that’s from his Milton, but from his later weird and visionary poem Jerusalem the Emanation of the Giant Albion which the poet Southey got a quick preview of in 1811, and ungratefully described as:

“a perfectly mad poem called Jerusalem” (from Kathleen Raine’s William Blake for Thames and Hudson).

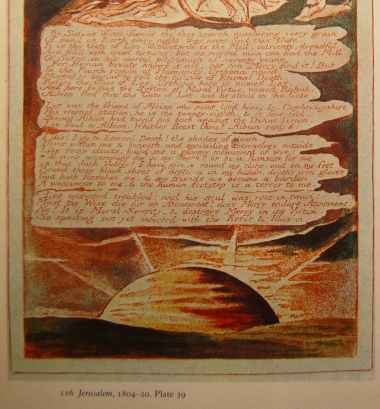

It seems that Blake worked on writing, designing, engraving and printing this book for over a decade, beginning perhaps in 1804 and continuing to add to the poem until 1820, and he illuminated only one copy, which he did not sell but was still in his possession on his death. Kathleen Raine gives us a way of understanding the work:

Blake’s ‘visions’ do not belong to time, but to the timeless; they are related as parts to a whole, but as parts of the surface of a sphere, all equidistant from the centre, rather than in the time sequence to which in this world we are normally confined. Like dreams they came to him in single symbolic episodes, or images; there is some attempt at chronology, but the material does not lend itself to this order, any more than would a series of vivid dreams, all relating, perhaps, to an unfolding situation, but not forming a consecutive narrative.

(How much this reminds me of the ‘unfolding’ situation now – and how prescient Blake’s vision, how all-encompassing!) And about his over-arching vision for the work itself:

A single inspiration informs words and decoration alike.

It is this unity of inspiration, and integrity of text and image that has always been my highest aim for my own work. I chose these particular words because they celebrate our patch – the area of London that is home for me and my partner – and because they seem to represent the most harmonious aspect of the city – benign and beautiful architecture on a human scale gracing fields as a natural evolution, rather than urban nightmare obliterating wasteland with ‘development’.

As I was making Blake’s London for my exhibition in the context of visions of London, including portraits of historic London houses and writers’ London landscapes, I wanted a very particular image to set the words within – an image that would be an embracing vessel for the text. I chose for this to draw Euston Arch – built in 1837, just ten years after Blake’s death, as the grand entrance way to the new Euston Station, gateway to the north – and embellished in 1870 with the letters E U S T O N cut into the architrave in letters of gold – and demolished in the new London of the 1960’s to the distress of many soulful Londoners including John Betjeman. I drew the arch from a contemporary photograph.

I thought that the arch’s golden pillars could here stand for the beautiful trees of Euston Grove, that wonderful green space surviving in front of the dark and dowdy Euston station. These huge trees are now over 200 years old, contemporary with Handel’s great plane trees of Brunswick Square, and have survived not only the bombs of the Blitz but the more insidious erosion of the constant traffic of Euston Road, the most fume-laden air in London – and played their part in protecting us Londoners from those fumes. And yet these trees are now threatened with demolition themselves, much to Londoners’ distress, to make way for HS2 building works. So the final lines stand as a plea, a spell, an invocation of Blake’s spirit to aid the hopeful vision of a future in which this particular green and pleasant bower may be spared the fate of Euston Arch.

I referenced Blake’s own design for the poem in making the work, composing the text layout inset into the image in little clouds, and the lettered font itself from one of the pages of Jerusalem in Blake’s own finished and illuminated copy:

And I followed the design for the starry sky in one of Blake’s watercolour drawings from his Illustrations of the Book of Job, in which The Morning Stars Sang Together, balanced like wing-walkers along God’s outstretched arms:

I like to think of those angelic morning stars shining through the branches of the great plane trees at Euston, still singing for us all.

Blake’s biographer the poet Kathleen Raine and the visionary painter Winifred Nicholson were great friends, so it seems appropriate to bring them together in this post, and finish with Kathleen Raine’s own view of the time and the city:

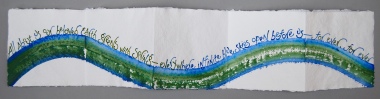

This is Blake’s Graffiti, a ‘banner-book’ made from driftwood, the ‘pages’ made from shards of a broken wooden wine-box we found washed up on the Thames foreshore near London’s Southbank Centre. The pages were first dried out, then bound together with linen book-binding tape and handmade paper, then painted and lettered with acrylic paints mixed with Thames water. The text is from Kathleen Raine’s poem What Message from Imagined Paradise; she could be writing it about today’s news – but I feel the message is perhaps ultimately comforting. Let’s focus on the delight as much as we can, and both hope and pray that we can ensure things change for the better after all this.

What message from imagined paradise

Can bring hope to us, whose daily news

Is of polluted forests, poisoned seas

Of the polluted air, the clouds

Laden with sour vapours from our furnaces;

What can we hope or pray for that can heal these

Mortal wounds to our brief beloved earth?

Implicit in each beginning is its end:

What poet can write

Of beauty truth and goodness in these days

(Or say rather, of what else?)

And yet I feel delight

As I look up into today’s blue skies

Where the sun still gives light

And warmth (wisdom and love, Blake says)

And on this doomed decaying city rise

On the last days as on the first

These marvels inexhaustible and boundless.

Kathleen Raine